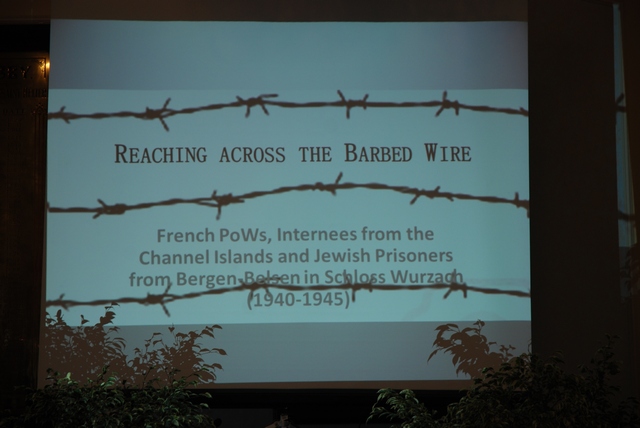

Jersey’s Book Launch of Reaching across the Barbed Wire

Sunday 23rd September 2012

Bad Wurzach

Gisela Rothenhausler at Liberation Square, with her Book “Reaching Across the Barbed Wire “of English families deported to Bad Wurzach during the occupation

PICTURE: TONY PIKE 21/09/2012

REF:01709202.jpg *** Local Caption *** Books

Gisela Rothenhuñusler

Sir Michael, Lady Birt, Constable Crowcroft, Ladies and Gentlemen, dear friends,

It gives me great pleasure to be given this opportunity to present my book about the internment camp where some 600 Jersey people had to spend nearly three years of their lives behind barbed wire. I want to invite you to accompany me on a short journey through my book to show you what perspective I have taken. I have set the history of the camp against the background of a considerable amount of European and Jersey history, so it has become a rather complex story which involves more than the Channel Islands and Nazi Germany.

In his diary from the concentration camp Bergen-Belsen, the Dutch lawyer Abel Herzberg describes a seemingly typical German mania: We are separated by barbed wire. It appears that the Germans possess a special predilection for barbed wire. Wherever you look barbed wire. Admittedly the quality is good, stainless. With long spikes, densely-set. …. Maybe the beards of the old Germanic men were already made of barbed wire. What macaroni is to the Italians, barbed wire is to the Third Reich.

This book has much to do with barbed wire just as the title suggests. I have even brought a piece of barbed wire from Wurzach which a local farmer took in 1945 from the barbed wire fence around the Schloss to make better use of it on his farm to fence in his cows. Today it might be a symbol, not for what separates us, but what has brought us together.

The internee artist who painted this picture probably had something different in mind, but I would like to interpret it as an anticipation of the future twinning, the internment in the Schloss serving as the foundation of friendship and a reminder that the past must never be forgotten.

When I came to Jersey in 2004 at the beginning of my research I did not know what I was embarking on. And Angela, who was organising a meeting with former internees, did not know either, fortunately, what role she was going to play. Originally I had aimed at a small brochure to explain to Wurzach townsfolk why we have this twinning with a town in an island so far away and in the end I was struggling to reduce the whole thing to a book of nearly 400 pages.

When I started I thought I was writing about a small part of local history of a small town in the south of Germany, close to the Alps (not in Bavaria), and some small islands off the coast of Normandy. But I learned quickly that if I wanted to do this properly I would have to have a closer look at the background and set the story into a larger context of European history which involved the United Kingdom, France and even Italy, the Netherlands and a lot of German and international offices and institutions. This is mirrored in the fact that I had to go to archives in France (in Paris and Colmar), in Switzerland, in the Netherlands, in Great Britain and of course in Jersey to collect my information, as the documentation in German archives is often incomplete.

The Schloss in Wurzach was built in the 18th century by the counts of Waldburg-Zeil-Wurzach and boasts to have one of the most beautiful staircases in Southern Germany. At the beginning of the 20th century the castle was rather run down and was sold to the Catholic community who set up a boarding school in the old building.

This aerial photo was taken in 1938 immediately before the beginning of the war and before the Schloss vanished behind barbed wire. The building had been modernised and extended. However, the seizure of power by the Nazis changed everything.

A Catholic school did not fit into the educational plans of the Nazis so it had to be closed.

As all the plans to find a civilian use for the Schloss came to nothing it was rented out to the German Wehrmacht for the purpose of a PoW camp. Harold Hepburn who has painted so many pictures of the internment camp made this picture from a postcard with the pre-war aerial view, which gives a good impression of what the camp looked like..

Just as with the fly-leaves we have used two matching pictures for the front and back cover of the book. The picture on the front, which was painted by Harold Hepburn for the wedding anniversary of Mr and Mrs Burges, shows the perspective of the local people in Wurzach, looking at the castle from the outside of the barbed wire fence. One of the distinctive features of Hepburn pictures was the flag with the Swastika, a steel helmet and a couple of British bomber planes.

And for the back cover of the book, we have used the view from the camp looking out onto the town. The back cover depicts the interaction that took place between the Schloss and the people on the other side of the fence.

The drawing was done by Antoine Pagni, a French prisoner-of war, who was just one of the first groups of prisoners to be housed in the Schloss from 1940 onwards.

And this is where Wurzach comes into the picture. The Italian Government contacted the German Foreign Ministry and asked to assemble all French PoWs of Corsican origin because they hoped they would be able to influence them and win them over for Italy. The Wehrmacht authorities were not at all enthusiastic about this project but complied and concentrated these prisoners in three camps in southern Germany, one of them the Oflag VC. This letter is an example of the extensive correspondence which expresses the dissatisfaction of the Corsican prisoners-of-war. Italian delegations were admitted to the camps and tried to convince the prisoners to change sides. But in all three camps the soldiers refused. They stated that they wanted to stay French and had no desire to become macaronis.

So the project was a complete failure and the Wurzach Oflag which was one of the smallest camps of this type was dissolved in 1942.

At this time the Wehrmacht were desperately looking for camps where they could accommodate a new group of prisoners they had never wanted to be responsible for: the deported people from the Channel Islands. The map shows Dorsten, Biberach, Laufen, Liebenau and Wurzach (and Kreuzburg in Silesia). This book does not deal with those Channel Islanders who were imprisoned in Germany for other reasons, so these prisons are not mentioned.

I think here in Jersey it is not necessary to describe the details of these days when the deportation order was published and executed. The German authorities never called it deportation they always labelled it as evacuation. I have described many events on the German side and explained why the original order from 1941 was not carried out until September 1942. Basically, it was a problem of too many different authorities with different interests involved and this was to remain a problem of the Channel Island internees and made their situation difficult.

This order from the Furhrerhauptquartier, the Furhrer’s headquarters, is, as far as I know, the only written evidence that can be traced back to Hitler himself. In the context of the fortification of the Channel Islands the order of the evacuation of the non-native islanders is announced, but no reasons given.

You will realise that this is the same border but filled with different pictures of camp life in Biberach. It is thanks to such paintings like this one by Mr Tipping or from the Webber family or by Harold Hepburn that we get a more vivid impression of camp life and add a lot of colour and illustration to my book although the pictures tend to show the more positive or funny aspects.

Biberach camp was considered overcrowded, so it was decided to move about 600 internees to the nearby camp in Schloss Wurzach which was empty after the Oflag had been disbanded Only Jersey people were moved to this other camp as the military authorities believed that much of the conflict in the Biberach camp were caused by the differences of the people from Guernsey and Jersey.

The remarks on this plan of the Wurzach Schloss camp were made by Michael Ginns who has helped me answer countless questions over the past few years. Some details are recognizable here.

Details of Room 56. There were big dormitories like this one: this is what home was now for the internees: some metal frame beds, some bunk beds, a few stools, maybe a shelf, but never enough room to store things much quarreling and strife resulted from these crowded living conditions.

View to the south, looking over the town, as seen from the second floor. If you look at the small pictures you see fancy names for the various meals available dishes which in reality were not fancy at all.

One of the difficult questions I had to struggle with was the question of responsibilities. Who was responsible? Who made the major decisions? Who reported to whom? What other positive or negative influences were there? I am convinced that it will be a surprise to you to see what an incredible number of authorities were involved, who wanted to take influence but were very reluctant to take responsibility; very often there were  even opposing interests. For the internees themselves it was very difficult to understand who had which power.

This picture shows the German Camp administration: It was headed by Commandant Police Leutnant Martin Riedesser. He was much respected by the internees as a strict but just commander and if they had been asked to name one good German he might have been their obvious choice. In marked contrast to this his superiors tended to blame him for every problem as he was at the end of the German chain of command this was easy for them. His deputy was Wachtmeister Abele. The rest of the guards consisted of policemen, usually elderly men, The prisoners of war in the Oflag had been guarded by roughly 200 soldiers! At no time were any SS troops stationed here, even though there continue to be persistent rumours to the contrary. The SS became involved in a totally different place.

The English camp administration: In Wurzach the Jersey internees were only referred to as the English, nobody knew about their Jersey origin, left alone that most of the people in Wurzach would not have known where to look for this island. The Head of the English camp administration was Captain Hilton and his Deputy Frank Ray. This is a fascinating piece of art it showed the internees gratitude for their camp seniors, and it also depicts all the various offices within the camp administration.

And now from foe to friend:

The British Government and the Channel Island authorities continued to do what they could for the internees well-being. Here it is a letter from the Foreign Office to the War Office dated April 1945 which shows a sketch of the camp in Wurzach, and which was drawn based on the feedback from the repatriated internees.

What was most important for the well-being of the internees was the International monitoring, according to the Geneva conventions.

Switzerland was the Protecting Power for over 30 countries, including Great Britain and the USA. The Swiss Protecting Power Department regularly visited PoW and internment camps, including those in Wurzach and Biberach. The reports about the situation in the camps were sent to the Home Countries. A truly important lifeline for the internees!

The internees were particularly grateful to the International Red Cross who ensured that thousands of food and clothes parcels were delivered; they also made regular visits to check on the wellbeing of the internees in the camp.

And finally, the Salvatorian priests played a role in the book. Some of you have met Father Hubert who is now provincial superior of the German Salvatorians. They were the owners of the Schloss, but they were not able to exert any influence. But they tried to help within their possibilities. After the war the Salvatorian priests have always welcomed former internees visiting the place of their internment.

A long chapter in the book deals with life in the internment camp, with the big number of problems, but also with the festivities and small joys.

Wurzach was a family camp; here is a picture of the playground in the front courtyard of the Schloss which was necessary as there were nearly 200 children and youths among the internees, enough to fill a school. The children from Room 56 alone could have filled one form, yet the lack of sufficient schooling was one of the major shortcomings in the Wurzach camp.

The internees devoted a lot of creativity to their artistic activities. They organised shows, theatre plays, musicals, exhibitions. Christmas and New Year festivities were prepared diligently, of course always hoping it would be the last one behind barbed wire.

The preparation for all these events was just as important as the event itself as this kept a lot of internees occupied. Boredom was the worst enemy of the prisoners in all the camps. Easter fashion. The materials for the costumes often came from the packaging material of the Red Cross parcels or from the YMCA Prisoner of War Aid who also supplied paper and colours without which we would not have all those marvelous pictures that help us to get an idea of camp life. This picture from 1942 shows us something the internees had to wait another two and half years to see, the Swastika flag on the ground..

Did internees have to work?

This was a fiercely contested problem. There was no discussion about work with respect to the upkeep of the camp.

Much more difficult was the question whether work for the Germans, the enemy, was acceptable. The internees were treated according to the Geneva Convention rules for prisoner of war officers, which meant they could not be forced to work. The Wurzach Camp Senior Hilton and the Biberach Camp Senior Garland, held the view that voluntary work was good for the internees, both physically and morally. Hilton even demanded a statement from the British Government. Indeed he received an answer from the British Legation in Berne which clearly stated that the British government did not disapprove of civilian work. Yet, those who did decide to work were severely criticised by their fellow-internees, but were rewarded by new friendships which in some cases lasted a life-time.

Sports

One major problem was the lack of exercise as the camp grounds were quite small considering the fact that there were about 200 children.

So finally groups of internees were permitted for walks outside the camps something that never happened in Biberach. It must have been a strange sight to see 100 or more internees like a procession, guarded by one or two policemen!. Frank Salmon describes on of these walks: Had a two-hour’s walk and a rest at the village pub, where we were allowed to have a glass of beer; nearly 150 of us bought up the whole stock. These walks indeed were an opportunity for contacts between internees and local people, especially for bartering: fresh vegetables, and fruit for biscuits, coffee and cigarettes from the Red Cross Parcel. One Wurzach lady told me that, as a child, she had always believed that the internees were rich people because they had such fancy things as chocolate and biscuits.One pub in a tiny near-by hamlet, the Hasen, was a particularly popular stop-off point. This village inn became a real barter headquarters. One of the guards would ensure that people knew at least a day before that the next internees walk would lead there. People who wished to do business just happened to drop in, buying the guard a beer whilst completing their transactions..

The internees showed much enthusiasm for sports events of all kinds. In April 1943, for example, there was a Sports Day with a wide range of competitions such as tug-of-war or potato races and many other events, like the three legged-race.

The lack of space was a permanent point of criticism in the reports of the Red Cross and the Protecting Power. And if you look at this layout of the Schloss and camp grounds you can easily guess what the delegates demanded. After the camp had been taken over by the Wurrttemberg Ministry of the Interior most of the barracks which had housed the guards of Oflag VC were empty and the Swiss delegates demanded again and again that these barracks and the empty grounds could be used by the internment camp. But these hopes were thwarted when in April 1943 new neighbours moved in: the Wehrerturchtigungslagera military training camp for Hitler Youth boys who were given ideological and military training.

Sanitary and medical conditions

This watercolour by Harold Hepburn shows the mens dormitory in the Schloss infirmary.

The internees were well looked after maybe better than it would have been possible in Jersey during the final years of occupation. Michael Ginns once told me that he did not believe his father would have survived the war in Jersey.

It is amazing to see what efforts were made for the internees. As late as 1945 there was a mass x-ray scheduled for all internees and routine exe-tests were carried out. The outcome resulted in some internees being surprised with a trip to Ravensburg where they were provided with glasses. This turned out to become a real outing, and one can hardly imagine a more paradoxical situation than a group of British civilian internees, who early in 1945 enjoy a day outing in Ravensburg. One of them reported. After this (test) we all went to a public house for dinner. We had several drinks, with soup, boiled potatoes and beetroot. After dinner we climbed up about 200 steps to the highest point in the town, so had a wonderful view of the district around…

And there were those that never returned home. 11 internees died in Wurzach and were buried in the Wurzach cemetery. And these graves actually formed the beginning of the reconciliation process. After the war, the Wurzach authorities took over the maintenance on the internees graves, but over the years lost their importance.

In 1966, a Wurzach citizen was ashamed to see the desolate state of the graves. In 1968 the internees graves were restructured with new headstones. And ever since the graves have been looked after by the town of Wurzach and each year we return to them to commemorate the events together.

And these graves lead to another story. There are 12 graves, but only 11 internees are buried here. And this is part of the story which people in Wurzach obviously had tried to forget and shows the problems of dealing with such a difficult history. Older people in Wurzach did occasionally refer to the English in the Schloss, but they never mentioned the 70 Jews who had been interned in the Schloss in the last months of the war. Alfred Miranda died two days after he had been transferred from Bergen-Belsen to Wurzach. The arrival of the first group of Jewish prisoners in November 1944 had a profound effect on the internees who realised that there were far worse places in Nazi Germany and maybe things were not so bad at Wurzach after all.

This is a long chapter in my book and was the most difficult part to research, as I did not have helpful eye-witnesses and collected material as in the case of the Jersey internees. But it is a very important part as it shows the differences in the Nazi camp system.

In 1943, the special concentration camp Bergen-Belsen was set up to which Jews in possession of western-allied passports were sent from all over Europe. These prisoners were held there for exchange purposes with Germans interned in foreign countries.  As most of the eastern European Jews had already been murdered, the search for suitable exchanges was carried out in the Netherlands. Approximately 3,500 people were deported from Westerbork to Bergen-Belsen because they had dual nationality Dutch and another, or passports from American countries, and were therefore potential exchange objects, even if the passports were quite obviously forged.

Himmler had planned for about 10,000 people to be exchanged this way, but only a very number of exchanges were indeed realised which saved these people from the hell of Bergen-Belsen. These few trains went south carrying people to Switzerland and from there onwards to Marseille.

This is what you can read in many books about the Holocaust and Bergen-Belsen, but that is the point where my story really starts.

For some of them the journey ended in Ravensburg because there was not an equal number of German exchange persons in the train waiting in Switzerland.  What a shock and disappointment this must have been, not far from the Swiss borders. But they were not returned to Bergen-Belsen, but taken to the Southern German internment camps to await the next exchange which never came for them.

I just want to take one person as an example. I had the privilege to get to know Irvin van Gelder. This shows him with Gwen and Maisie and he is explaining the lay-out of Camp Westerbork. Irvin was seventeen when he arrived in Wurzach in November 1944 and weighed just 34 kilograms which earned him the nickname skin and bones. In 2005, when we commemorated the 60th anniversary of the end of the war, he said in a spontaneous speech: I came from hell into heaven, in Wurzach I was reborn. He died in 2009, but in Wurzach he is remembered as one of those who extended their hand for reconciliation.

The family van Gelder had a rightful claim to American passports because the father, Henry van Gelder, was born in the USA. His only proof was a copy of the registration of his birth from Baltimore and confirmation from the Swiss Legation that he had requested the American documents.They did not even have the American confirmation of their request or even passports but this was sufficient to be sent to Bergen-Belsen. But, yet, they still needed a lot of luck to be included in an exchange a lot of Jews with valid passports were not included and were murdered in the death camp.

This Christmas card already shows the hopes for an early return home and the new friendships in the Schloss.

There are only a few pictures of the liberated internees, here the Peacocks at the centre with the Wurzach butcher Ries whom they had befriended during their internment. Frank Ray, the deputy camp senior, was made provisional mayor of Wurzach by the French and he kept this post until the beginning of June when the internees were repatriated.

And this is where the reconciliation process actually started older Wurzach townsfolk have always been grateful to Captain Ray as they were convinced that they owed him the comparatively peaceful beginning of the post-war period.

To put it into a nutshell, the book is all about the internment camp Let me sum up what the book is all about: It is the story of the internment camp and all these different issues are mere footnotes of the history of WW II, but they have shaped our present…

… and the reconciliation process.

But above all, it is about real people suddenly involved in war events and about what positive things can grow out of such a gloomy background. Former internees here in Jersey, as well as in Guernsey, have worked so much for the reconciliation process and the twinning which has brought us so many wonderful encounters.

And finally I would like to express my thanks. Actually there is a very long list of people who have given me help, I can’t mention them all, but I want to mention some. Above all I would like to express my gratitude to all the former internees who patiently answered my questions, my correspondence with Michael Ginns could fill a book ………

Sir Philip Bailhache who encouraged me, way back in 2006, to write this book and then translate it!

Sir Michael who supported the English edition of the book

… and Angela who spent years of her life working for the twinning. She was convinced the book should be translated and volunteered to do the translation with me. Had she known what this meant I am sure she would never have done it. We had to find out how much hard work it is to translate such a book, with all those military and technical terms.

My sincere and heartfelt thanks also to Paula Thelwell who did the sub-editing with me and her job was to make sure that this book can be read and understood by a British reader.

And Tony Pike has kindly assisted with so many pictures he has taken for me and during the many events of our twinning

Simon as the host of these festivities and many, many other people

And finally, my sincere thanks to everyone for being here today.